Beyond the Cloud: CapEx vs Subscription TCO Analysis - Part I

Which stack is cheapest over five years for a 100 VM footprint? A detailed TCO analysis of Hyper-V, Azure VMware Solution, and Azure Local.

Introduction

In our previous blog post, we explored why organizations are reconsidering their virtualization strategy post-VMware and highlighted the often-overlooked value of Windows Server Failover Clustering with Hyper-V. Now, in this first follow-up post of the "Beyond the Cloud: The Case for On-Premises Virtualization" series, we dive into the financial side of that decision. Specifically, we will compare the five-year Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) for three possible platforms to run a 100-Virtual Machine (VM) workload:

- On-Premises Hyper-V (traditional Capital Expenditure (CapEx) model)

- Azure VMware Solution (AVS – cloud subscription model)

- Azure Local (formerly Azure Stack Hyper-Converged Infrastructure (HCI) – hybrid model)

Our goal is to determine which stack delivers the lowest TCO over a five-year span and how the cost structures differ between upfront capital expenses and ongoing subscription-based expenses. We’ll base our comparison on a realistic small-to-midsize environment (around 100 VMs) and include all major cost components: hardware, software licenses, support contracts, and cloud service fees. Let’s set the stage with our assumptions about the environment and then break down the costs for each option.

Series Navigation

- Introduction: Beyond the Cloud: Rethinking Virtualization Post-VMware

- Part I: Beyond the Cloud: CapEx vs Subscription TCO Analysis (This Post)

- Part II: Beyond the Cloud: 2025 Virtualization Licensing Guide

- Part III: Beyond the Cloud: Hardware Considerations

- Part IV: Beyond the Cloud: Feature Face-Off - Part IV

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Series Navigation

- Table of Contents

- Scenario Assumptions: The 100-VM Environment

- TCO Cost Components

- Option 1: On-Premises Hyper-V (Windows Server) – CapEx Model

- Option 2: Azure VMware Solution (AVS) – Subscription Model

- Option 3: Azure Local (formerly Azure Stack HCI) – Hybrid Model

- Five-Year Cost Comparison

- Other Considerations (Beyond Raw TCO)

- Conclusion: CapEx vs. Subscription – Which Wins?

- References

Scenario Assumptions: The 100-VM Environment

To make this comparison concrete, we’ve modeled a representative Information Technology (IT) environment of 100 virtual machines. This environment includes a mix of infrastructure and application workloads that a typical mid-sized organization might run:

- Core infrastructure services (~10–15 VMs): Active Directory domain controllers, Domain Name System (DNS) and Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) servers, a file server, an Exchange or email relay server, and other necessary support services. These tend to be small-to-medium VMs (2–4 virtual Central Processing Units (vCPUs), 4–8 Gigabytes (GB) Random Access Memory (RAM) each).

- Line-of-business application servers (~20–30 VMs): Application middle-tier servers and internal services (e.g. an Human Resources (HR) system, finance apps, intranet apps). These vary in size, with many around 4 vCPUs and 8–16 GB RAM, and a few heavier ones.

- Web and front-end servers (~10–15 VMs): Front-end web servers or Application Programming Interface (API) endpoints, load-balanced for external or internal web applications. Typically lighter VMs (2–4 vCPUs, 4–8 GB RAM) but several instances for redundancy.

- Database servers (~5–10 VMs): A handful of database servers (e.g. Structured Query Language (SQL) Server or similar) supporting the above apps. These are among the larger VMs (8+ vCPUs, 32+ GB RAM, with one or two high-memory instances).

- Other miscellaneous servers (~10+ VMs): This includes dev/test servers, logging/monitoring systems, backup servers, and maybe a few virtual desktops or Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) session hosts. Sizes vary.

Overall, the workload is predominantly Windows Server–based (typical in a Microsoft-centric shop), with perhaps a few Linux appliances or open-source tools. We assume moderate utilization – in aggregate, the 100 VMs might consume on the order of ~1 to 1.5 Terabytes (TB) of RAM and a proportional amount of Central Processing Unit (CPU) cores when consolidated. This assumption will drive how much physical infrastructure is needed (for on-premises scenarios) or how many cloud nodes are required (for AVS).

Physical Infrastructure Assumption: For on-premises deployments (Hyper-V or Azure Local), we assume a cluster of 3 host servers is used. Three hosts provide high availability for maintenance and failover, and can comfortably support ~100 VMs given the spec we assume (modern 2-socket servers). Each host server is assumed to have roughly 2×16-core CPUs (32 cores total), plenty of RAM (e.g. 512–768 GB per host), and fast Solid State Drive (SSD)/Non-Volatile Memory Express (NVMe) storage (sufficient to hold all VM data in a hyperconverged setup). This spec aligns with a mid-range 1U or 2U server that organizations commonly deploy. We’ll include the cost of these servers (with storage included) as a capital expense in the on-prem models. We also assume enterprise support/warranty is purchased for the hardware for 5 years. Networking gear (switches) and data center facility costs (power, cooling, rack space) are not explicitly priced in our model, though we will discuss them qualitatively later on. Including those would increase on-prem costs slightly, but for simplicity we focus on the major cost drivers.

With the stage set, let’s break down the TCO for each option in detail.

TCO Cost Components

Before diving into each scenario, it’s important to outline the cost components we’ll be considering in our five-year TCO analysis:

- Hardware Costs (CapEx): Upfront purchase of physical servers and storage. For on-premises Hyper-V or Azure Local, this is the purchase of host servers (in our case, 3 nodes) and associated storage devices. We assume an initial capital expense that covers the hardware and includes a support contract (typically, vendors offer 3-5 year support/warranty with hardware purchase or as an add-on). In the AVS scenario, there is no upfront hardware purchase – the hardware is provided as part of the service.

- Software and Licensing Costs: This includes operating system licenses, hypervisor or virtualization software licenses, and any other required software for the virtualization stack. For Hyper-V, the key license is Windows Server (which includes Hyper-V at no additional cost). For Azure Local (formerly Azure Stack HCI), licensing can be handled in two ways: either via a monthly subscription fee per core to Microsoft, or by leveraging existing Windows Server licenses with Software Assurance (SA) (via Azure Hybrid Benefit (AHB)) to cover the host OS fees. We will examine both approaches. For AVS, the VMware software (vSphere, vSAN, NSX, etc.) licensing is included in the AVS service pricing, so you don’t separately buy VMware licenses – however, you may still need Windows Server licenses for the guest VMs (unless you use AHB there as well, which we’ll note).

- Support and Maintenance Contracts: Ongoing support costs for software and hardware. In on-prem scenarios, this could include hardware support contract renewal (if not covered for the full 5 years upfront) or software support subscriptions. In our model, we’ll assume the hardware support is prepaid upfront (common in enterprise purchases) and that software support for Windows is either included via Software Assurance or a portion of the license cost. AVS, being a fully managed service, includes support for the infrastructure in its monthly price.

- Operational Expenses / Cloud Service Fees (Operational Expenditure (OpEx)): These are the recurring costs paid over time. For pure cloud (AVS), this is the monthly service charge for the AVS nodes. For Azure Local, if using the subscription model, this is the monthly fee per physical core for the cluster, and any additional Azure services used (the base fee covers the infrastructure software). For on-prem Hyper-V, there is no analogous monthly hypervisor fee – once you’ve bought Windows Server licenses, you can run Hyper-V with no ongoing fee. (Of course, there are operational costs like electricity, cooling, and IT staff time, but those are generally outside the scope of a straightforward TCO financial model. We’ll discuss them qualitatively later on, as they can tilt decisions in specific cases.)

With these components in mind, let’s analyze each option one by one.

Option 1: On-Premises Hyper-V (Windows Server) – CapEx Model

What it is: This is the traditional deployment of a Windows Server Failover Clustering (WSFC) with Hyper-V on your own hardware. You buy servers, install Windows Server (with the Hyper-V role), and run your VMs on this cluster. This option is heavy on capital expenditure upfront but relatively light on ongoing costs. It exemplifies the CapEx model: invest in hardware and perpetual licenses now, then operate with minimal fees going forward.

Infrastructure & Hardware: We assume a 3-node cluster of identical servers. Each server might cost on the order of $15,000 (give or take) depending on configuration – for a total hardware investment of roughly $45,000. This would include high-performance local SSD/NVMe storage in each host (using Storage Spaces Direct for a shared-nothing, hyperconverged setup), and 10–25 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) network interfaces for cluster communication. The cost also typically includes 3-5 years of vendor hardware support (parts replacement, firmware updates, etc.). By leveraging existing data center networking and facilities, these servers are all you need to stand up the Hyper-V environment.

Licensing Costs: One of Hyper-V’s biggest advantages is that it comes “free” with Windows Server. In practice, that means if you have licensed your hosts with Windows Server Datacenter Edition, you have the rights to run unlimited Windows Server VMs on those hosts at no extra charge for the OS in each VM. Datacenter Edition is the logical choice for virtualization-heavy scenarios like 100 VMs on 3 hosts. We estimate you’d need to license each host for its cores: e.g., 32 cores per host. Microsoft sells licenses in 16-core packs, so each host needs two packs (covering 32 cores). Roughly speaking, a 16-core Windows Server 2025 Datacenter license has a Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price (MSRP) around $6,000-$6,600. So for 32 cores that’s $12,000-$13,200 per host, times 3 hosts = $36,000-$39,600 in Windows Server licensing. (Enterprise agreements or cloud solution provider pricing could be lower, but we’ll use list prices for a fair comparison.) This $36K-$40K gives us the rights to run our 100 VMs (assuming they are Windows Server guests) without needing separate licenses for each VM – a huge cost win for Hyper-V on Windows. Hyper-V itself has no additional cost; it’s simply a role of Windows Server. We are also implicitly covering the cost of Hyper-V management tools – many shops would use Failover Cluster Manager and Windows Admin Center, which are free, or possibly System Center Virtual Machine Manager (SCVMM) if they have it licensed as part of a System Center suite. To keep things simple, we won’t add System Center licensing here, since it’s optional.

Support & Maintenance: With Windows Server Datacenter, you typically get rights to new versions and support if you have Software Assurance (SA) on the licenses. Some organizations purchase SA (which is an annual fee, ~25% of license cost) to ensure they can upgrade to the latest Windows Server release or get 24/7 support from Microsoft. Others might skip SA for cost savings if they don’t plan to upgrade frequently. For our model, let’s assume the $36K for Windows licensing is a one-time cost that includes at least the ability to use the licenses for 5 years. We’ll not separately charge for SA, since not all will use it, but note that if you do pay SA, that might add roughly $7K–$9K per year across all 3 hosts. (However, in a purely cost-focused analysis, many would forego SA and stick with a stable version of Windows Server to avoid that recurring cost.)

Hardware support is assumed to be included for 5 years from the server vendor (either as a standard package or an extended warranty purchased upfront). Thus, we don’t add an extra annual support fee for hardware. The environment will incur some ongoing operational costs like power/cooling and administrator time, but those are outside our financial calculation here – though you should remember to factor them qualitatively when comparing to cloud (where power/cooling are baked into the price).

Five-Year TCO Summary (Hyper-V): Virtually all costs are upfront in year 0: about $45K in hardware and $36K-$40K in licenses, totaling roughly $80–$90K initial investment. Over the subsequent 5 years, the ongoing costs are minimal – primarily maintenance of what you bought. There are no cloud bills or monthly fees. At the end of five years, you may consider refreshing hardware or renewing support, but within that span no major new costs arise. This one-time investment approach is why Hyper-V/Windows Server Failover Clustering (WSFC) on existing licenses is often cited as the lowest TCO option for running VMs, assuming you can amortize the upfront spend. In short, CapEx-heavy now means savings later. Many Microsoft-aligned organizations find this especially attractive since they “already paid for Windows”, so to speak.

Option 2: Azure VMware Solution (AVS) – Subscription Model

What it is: Azure VMware Solution is Microsoft’s managed service that runs VMware vSphere environments in Azure data centers. Essentially, you rent a private cloud in Azure that is pre-loaded with VMware’s software, and you deploy your VMs on it just as you would on-prem vSphere – except you’re paying Microsoft a subscription fee for the infrastructure and VMware licenses. This option is pure OpEx (operational expense): you pay as you go, with no need to buy hardware or perpetual licenses upfront. It’s designed to quickly “lift and shift” VMware workloads to the cloud with minimal changes.

Infrastructure & Scaling: AVS is sold in units of hosts (nodes). Each host is a physical server in Azure dedicated to you, with a fixed amount of vCPU, RAM, and storage. Azure offers several host size options (for example, an “Azure VMware Solution 36-core (AV36)” node has 36 cores, 576 GB RAM, ~15.2 TB usable storage; an “Azure VMware Solution 36-core Plus (AV36P)” offers more RAM (768 GB), an “Azure VMware Solution 52-core (AV52)” has 52 cores and 1.5 TB RAM, and the newer “Azure VMware Solution 64-core (AV64)” has 64 cores and 1 TB RAM, etc.). The service requires a minimum of 3 hosts to form a vSphere cluster with resiliency. For our 100 VM scenario, a 3-node AVS cluster is the starting point. According to Microsoft and partners, AVS becomes reasonably cost-effective at around 100–150 VMs – basically, if you can fully utilize those 3 nodes with ~100+ VMs, the cost per VM is in a tolerable range. With fewer VMs, you’d be under-utilizing an expensive 3-node minimum footprint. We’ll assume our 100 VMs fit within 3 AVS hosts (likely the AV36 or AV36P specs should handle it).

Cost Structure: AVS pricing includes everything for the virtualization layer: the compute hardware, VMware Elastic Sky X Integrated (ESXi), VMware vCenter, VMware Virtual Storage Area Network (vSAN) storage, NSX Transformers (NSX-T) networking, and even VMware Hybrid Cloud Extension (HCX) for migration are all bundled. VMware licensing costs are included in the Azure price – meaning you’re not separately paying VMware (Microsoft handles that relationship). However, Windows Server guest OS licenses are NOT included by default in AVS. If you run Windows VMs on AVS, you have two choices: bring your existing Windows licenses via Azure Hybrid Benefit (which most will, since they likely had Windows licenses on-prem), or pay Azure for Windows Server just like you would for an Azure VM (AVS allows you to tag VMs to have Windows licensing billed). In our comparison, we’ll assume you utilize Azure Hybrid Benefit for Windows VMs on AVS, since our on-premises scenario already assumed we owned Windows licenses. That lets us focus on the core infrastructure costs.

AVS is billed per host, per hour (or per month). It’s not cheap. To give a ballpark, in the East United States (US) region, a typical AV36 host on pay-as-you-go costs on the order of $6–8 per hour, which is around $5,000–$6,000 per month per host. Three hosts would be roughly $15,000–$18,000 per month at list price. This aligns with public figures: in the United Kingdom (UK), pay-go for 3 nodes is about £18,500/month (≈$23K), and one user reported in East US their 3-node estimate around $22K/month. Microsoft offers substantial discounts for committing to 1-year or 3-year reservations – on the order of 30-50% off. In fact, currently a 3-year reserved instance for AVS can slash the cost by ~60% compared to hourly rates. Using the UK example, 3 nodes dropped to ~£9K/month with a 3-year commit. In US terms, we can assume maybe around $10K–$12K per month for a 3-node AVS cluster on a multi-year reservation. We’ll use $10K/month for 3 nodes as a nice round figure for our 5-year TCO, assuming the organization locks in a reserved term to optimize cost. (Microsoft even introduced a 5-year reservation option with similar ~60% savings, which would align with our 5-year analysis horizon.)

Five-Year TCO (AVS): At $10K per month for the AVS cluster, the 5-year cost is $600,000. Importantly, there’s no upfront CapEx – you start paying when you turn on the service, and if you ever turn it off, the billing stops (though if you reserved capacity, you’ve committed to pay for the term whether you use it or not). Over 5 years, however, that adds up drastically: AVS is by far the most expensive option in terms of raw dollars outlay in our comparison. Even if we hadn’t assumed a discount, pay-go rates would put it closer to $1M for 5 years; with reservations we got it to $600K. This cost includes support and all infrastructure, but it does not include certain things like backups or bandwidth charges (if you egress a lot of data out of Azure, that’s extra) – those are beyond our scope here.

To put it in perspective, when comparing cloud vs. on-premises, studies and anecdotes often find that steady-state workloads (like our 100 VMs running 24/7) are 3–5× more expensive in the cloud than on-premises equivalents. Our model indeed shows roughly an order-of-magnitude difference: $80K vs. $600K in five years (that’s ~7.5×). Even if our on-premises costs were higher or we included data center expenses, the cloud cost remains several times higher. Why would anyone pay this premium? The reasons usually cited are business agility, shifting to OpEx, and offloading maintenance overhead. With AVS, you avoid having to purchase or maintain hardware, deal with hardware failures, or perform lifecycle management of VMware software – Microsoft handles those under the hood. If your company is “CapEx sensitive” (i.e., has no stomach or budget for large upfront spends) but has monthly OpEx budget, AVS could be attractive despite the higher 5-year price. Additionally, AVS can simplify disaster recovery and scaling: you can add more hosts on demand (within a few hours) and even spin down hosts if not needed (billing is monthly granularity). Those capabilities might save money in certain scenarios (like temporary dev/test clusters or seasonal bursts), but for a steady 100-VM footprint we aren’t factoring that in.

In summary, AVS offers a cloud-first, subscription approach – convenient and fast to deploy, but you pay a hefty premium for that convenience. It is essentially the opposite end of the spectrum from the Hyper-V CapEx model in cost structure.

Option 3: Azure Local (formerly Azure Stack HCI) – Hybrid Model

What it is: “Azure Local” is Microsoft’s newer hybrid cloud infrastructure stack that you run on-premises (or at the edge) but pay for via an Azure subscription. Azure Local uses the same Hyper-V hypervisor and Windows-based clustering concepts, but it’s delivered as an Azure service: you install the Azure Local operating system on your servers and register the cluster with Azure. It’s a bit of a blend between the first two options – you do purchase your own hardware (like the Hyper-V scenario), but instead of a one-time Windows Server license, you typically pay a monthly fee per core to license the Azure Local operating system. This gives it a cloud-like subscription cost model, even though the hardware is your own (CapEx). Microsoft positions Azure Local as their “premier” on-premises solution with cloud integration, hence the Azure branding.

Note on Current Naming: Microsoft has rebranded Azure Stack HCI as “Azure Local” starting in late 2024, though both terms are still used interchangeably in documentation and pricing.

Infrastructure: The hardware for Azure Local would be very similar to the Hyper-V case – likely the same 3 servers could be used (just with a different OS installed). In practice, Azure Local requires validated hardware from an approved vendor list (approximately 200+ validated node configurations). These tend to be newer, high-end servers – you usually won’t run Azure Local on decade-old hardware. This means an organization might need to purchase new servers to adopt Azure Local, rather than repurposing older ones (which they might have done if sticking to Windows Server 2019/2022). Microsoft also offers integrated systems or vendor appliances for Azure Local that come with Azure Local pre-installed, sometimes on a hardware-as-a-service financial model, but for apples-to-apples comparison we’ll assume standard purchase of similar 3 nodes (~$45K hardware cost as before). So the CapEx for hardware (~$45K) is essentially the same as Option 1. Where things differ is in software licensing and ongoing fees.

Licensing Options: There are two ways to license the software for Azure Local:

Pay-per-core Subscription (OpEx): By default, Azure Local clusters are billed at $10 per physical core per month (or roughly €10 in European Union (EU) as cited). This is the host fee for the Azure Local service. In addition, if you want to run Windows Server guest VMs and you don’t have existing licenses, Azure offers an add-on subscription for those as well: about $23.30 per core per month for unlimited Windows guest licensing rights on the cluster. Essentially, $10 covers the host hypervisor and cluster features, and another $23 covers Windows Server Datacenter rights for the VMs – bringing it to roughly $33 per core per month to fully license everything via subscription. Importantly, these fees are charged only as long as the cluster is registered; if you retire the cluster, the billing stops. If you have Linux VMs or other workloads, you might not need the guest OS subscription for those cores, but typically in a mixed environment you’d likely license all cores for simplicity so any VM can run anywhere. This pure subscription approach turns your on-prem infrastructure into an operational expense much like cloud. However, as we’ll see, over 5 years it adds substantial cost.

Azure Hybrid Benefit (AHB – Bring Your Own License, CapEx): Microsoft recognizes many customers already have Windows Server Datacenter licenses with Software Assurance. With Azure Local, they provide an option to apply those licenses to cover the fees. If you have Windows Server Datacenter + SA for your host cores, you can activate Azure Hybrid Benefit for Azure Local, which waives the $10/core host fee and the Windows guest licensing fee. In other words, by “bringing your license” you don’t pay Azure anything for the Azure Local OS or for Windows Server VMs – you’ve effectively paid upfront by buying the Windows licenses. The trade-off is you must keep your Software Assurance active (which typically means renewing it every couple of years). SA is not free – it’s an ongoing cost (roughly 20-25% of the license cost per year) – but even so, this route often comes out cheaper than paying the full Azure metered rate continuously. Microsoft has explicitly noted that for customers with SA, Azure Local’s costs drop dramatically, making it “even more competitive from a cost point of view” compared to other platforms.

Let’s quantify these: We have 3 hosts × 32 cores = 96 cores total in the cluster. Under the pay-per-core model, host fees would be 96 × $10 = $960/month, and Windows guest subscription (if needed for all cores) 96 × $23.3 ≈ $2,237/month. Combined ~$3,197/month. Over 60 months (5 years), that’s about $192K in fees. (If some VMs were Linux, one could save on the guest fee proportionally, but our scenario is predominantly Windows.) Add the $45K hardware, and the 5-year total is roughly $237K. This is the “fully subscription” cost scenario for Azure Local.

By contrast, under Azure Hybrid Benefit model, we’d reuse the same $36K-$40K of Windows Datacenter licenses from Option 1. As long as those licenses have active SA (which might cost say $7K-$8K/year), over 5 years that SA might total $35K-$40K. So effectively, you pay $36K-$40K (licenses) + $35K-$40K (SA maintenance) + $45K (hardware) = $116K-$125K total. However – and this is key – many organizations already count Windows licensing as a sunk cost or part of their enterprise agreement. If that’s the case, enabling AHB could mean no new spending at all on software. For simplicity, one could say $80–$90K (hardware + licenses) covers 5 years when using AHB (very similar to the pure Hyper-V scenario). In fact, if the company already owned Datacenter licenses (perhaps repurposed from an older cluster), the incremental cost might be just hardware. Azure Local in this mode essentially becomes a CapEx model hiding behind Azure branding. You still benefit from the fact that the OS is updated frequently (as a service) and deeply integrated with Azure management, but you’re not paying monthly for the privilege – you paid upfront.

It’s worth noting that there is now also an Azure Local “Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) perpetual” licensing option some hardware vendors offer, where you can buy a one-time license for the Azure Local host (much like buying Windows Server). This is essentially another way to pre-pay for the Azure Local software if you don’t want any ongoing subscription. That option is new and offered through partners, but since it ultimately will price out similar to using AHB (capex licensing), we won’t delve deeply into it here.

Five-Year TCO (Azure Local): We effectively have two sub-scenarios:

Azure Local with Pay-Go Subscription: Approx. $240K over 5 years for 96 cores (plus hardware). This lands in between the Hyper-V and AVS costs. It’s about 3× the cost of the pure Hyper-V approach, but still significantly less than AVS. Why is it cheaper than AVS? Because you’re only paying Microsoft for software, not for hardware markup or data center electricity. $10/core/month is roughly $300/year per core, so for a 32-core host that’s $9,600/year. Compare that to an AVS host which might be $60K/year – clearly running your own servers saves money. However, $240K is still a lot more than $80K; that difference is basically the price of having a “cloud-like” constantly updated platform. As some critics have pointed out, if you run Azure Local for many years without leveraging those continuous updates, you might be over-paying versus a one-time Windows license.

Azure Local with AHB (Bring License): Roughly $80–$130K over 5 years (depending on whether you count SA costs), which closely matches the on-premises Hyper-V TCO. In essence, using AHB turns Azure Local into just another usage of your Windows Server licenses – you’ve converted the expense back into CapEx. In our case, if we re-use the same $36K-$40K of licenses from Option 1 and pay maybe $8K/year in SA, we’d spend $36K-$40K + $40K + $45K hardware ≈ $121K-$125K. If the org already had an Enterprise Agreement (EA) covering Windows SA, the effective incremental might just be the hardware $45K. The bottom line: with AHB, Azure Local’s cost model can be as low as traditional Hyper-V.

It’s important to mention that with Azure Local you do get some additional capabilities for that cost: for example, integration with Azure Arc for management, eligibility to use Azure’s hybrid services (like Azure Backup, Azure Monitor) more seamlessly, and the advantage of frequent feature updates (Azure Local gets new features every year, whereas Windows Server Hyper-V is now feature-stable with only periodic Long-Term Servicing Channel (LTSC) releases). However, those benefits need to justify the ongoing fees. If an organization is content with a “stable and done” infrastructure, the one-time license model is often cheaper. Microsoft essentially offers both choices: pay continuously for the latest-and-greatest, or use your existing license to opt out of the meter. Our analysis shows how each choice impacts TCO.

Five-Year Cost Comparison

Bringing all three options together, let’s compare their 5-year TCO side by side. We’ll consider Azure Local in its subscription mode for the main comparison (since Hyper-V covers the license-included mode already).

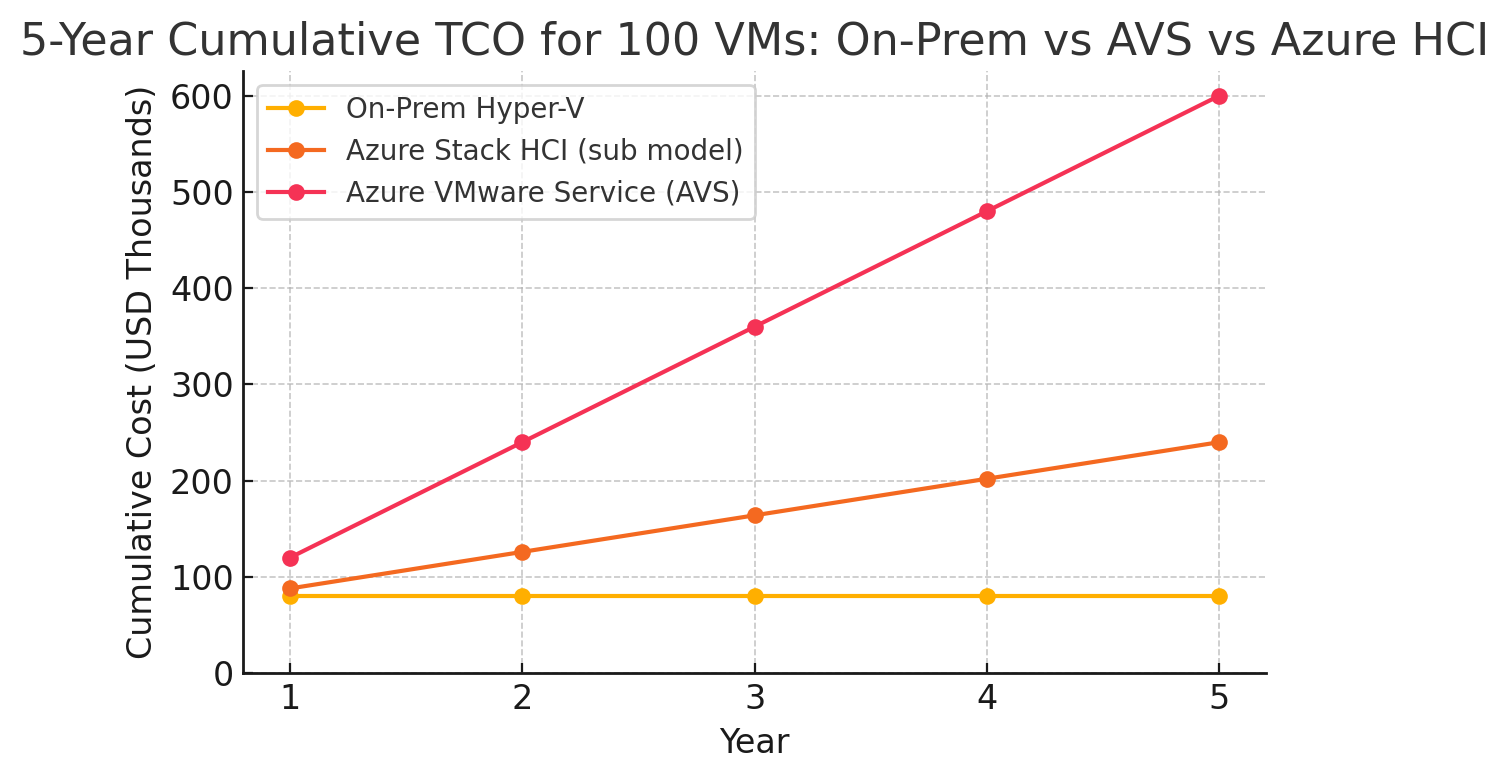

Five-year cumulative TCO for running 100 VMs under three different models. On-premises Hyper-V (yellow) has a high initial CapEx but minimal increase over time. Azure Local with pay-go subscription (orange) starts with some CapEx (hardware) and grows with monthly fees. Azure VMware Solution (red) has no upfront cost, but a steep ongoing cost that far exceeds the others over 5 years.

The chart illustrates the cumulative spending over five years. You can see that Hyper-V’s line flattens out early – after the initial purchase in Year 1, there’s little incremental cost. Azure Local (pay-go) rises steadily, ending around 3× higher cost by Year 5 than Hyper-V. AVS’s cost line is the steepest by far – it ends up roughly 7× higher than the Hyper-V option by Year 5. Even if we assumed some savings or scaled down nodes in AVS, it would remain dramatically more expensive in this steady-state scenario. This aligns with real-world observations that running constant workloads in the cloud is typically multiple times costlier than owning your infrastructure.

For another perspective, consider the breakdown in a tabular form:

| 5-Year Cost Component | Hyper-V On-Prem (CapEx) | Azure Local (Subscription) | Azure VMware (AVS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware (3 hosts) | approx. $45,000 (one-time) | approx. $45,000 (one-time) | $0 (included in service) |

| Base virtualization software | $0 (Hyper-V is included in Windows Server) | approx. $10/core/month = approx. $57,600 over 5 yrs (96 cores) | $0 (VMware licenses included in AVS price) |

| Windows Server OS for VMs | approx. $36,000-$40,000 (one-time for Datacenter licenses covering unlimited VMs) | Option A: approx. $134,000 over 5 yrs via sub (96×$23.3/core/month); Option B: $0 (if using existing licenses via AHB) | $0 (existing Windows licenses can be applied with AHB on AVS) |

| Support & maintenance | Included in above (hardware warranty; Windows support via SA optional) | Included in above (hardware warranty; Azure support in core fee) | Included in service (Azure support covers infrastructure) |

| Total 5-Year TCO (approx.) | approx. $80–$90K | approx. $240K (if fully pay-go) or approx. $80–$130K (with AHB) | approx. $600K |

Assumptions: The table assumes 96 cores total. Azure Local “Option A” reflects pure pay-as-you-go for all software; Option B reflects use of existing licenses (Azure Hybrid Benefit) to eliminate the ongoing software fees (making it analogous to Hyper-V’s one-time licensing). Windows guest OS costs for AVS are assumed covered by AHB (since the organization could re-use the same licenses from the Hyper-V scenario – otherwise AVS would charge per VM, increasing its cost even more). Dollar figures are rounded. Note that Windows Server 2025 pricing reflects a modest increase over 2022 versions.

Looking at the “Total 5-Year TCO” row, a clear ranking emerges: On-premises Hyper-V (and Azure Local with AHB) are the cheapest, on the order of <$100K for 5 years. Azure Local with subscription comes next, roughly 2.5–3× higher. AVS is the most expensive, roughly 6–7× higher than the cheapest option in absolute dollars. In relative terms, Hyper-V/Windows Server Failover Clustering (WSFC) is the winner in cost-efficiency, assuming one is willing and able to make the upfront investment and has the skillset to manage it. Azure Local gives the flexibility to go either way: use it like a subscription service (incurring higher TCO) or leverage your existing licenses to keep costs low. Azure VMware Solution squarely targets convenience and speed over cost – it’s for organizations that accept a higher ongoing cost in exchange for not retooling their operations or not spending capital upfront.

Other Considerations (Beyond Raw TCO)

While cost is the focus here, it’s worth briefly noting other factors that might influence a choice between these options despite the stark TCO differences:

Existing Investments & Skills: If you already have heavily invested in VMware expertise and tooling, AVS allows you to retain that – your admins keep using vCenter, and your processes remain largely the same. Moving to Hyper-V or Azure Local might involve retraining staff or redeveloping automation for a new platform (though Hyper-V is similar enough for a Windows admin to learn, it’s still a change). This “skills transition” factor often justifies AVS as a stop-gap even if it’s more expensive. Conversely, if your team is already Microsoft-focused, staying on Hyper-V or Azure Local is not a burden at all – it plays to your strengths.

Feature and Integration Differences: Azure Local is continuously updated and tightly integrated with Azure services (Azure Arc management, Azure Backup, etc.) out of the box. It also supports Azure Kubernetes Service on-prem, etc. If those hybrid capabilities are valuable, an organization might lean towards Azure Local even if it costs more than plain Hyper-V, because it aligns with a cloud-first strategy (just on your own terms). On the other hand, plain Hyper-V on Windows gives you total flexibility with hardware and the lowest software cost, but it lacks some of the fancy cloud integration unless you configure Azure Arc manually.

Scaling and Right-Sizing: With your own hardware (Hyper-V or Azure Local), you have fixed capacity once you buy it. If you over-provision, money is wasted; if you under-provision and need more, you have to buy more hardware (which could take time and more CapEx). AVS offers more elastic scaling – you can add a host for a few months and then remove it (with some notice) if needed, turning a capital problem into a scheduling problem. For steady workloads, this isn’t very advantageous, but for variable or unpredictable growth, AVS (or even Azure Local if financed monthly) could prevent overbuying. That said, adding one more on-prem Hyper-V node is not terribly difficult if growth is expected – you just need to plan for it.

Data Center Costs: As hinted earlier, on-premises solutions come with “hidden” costs like power, cooling, physical space, and on-site personnel. In a large enterprise these are often amortized or considered sunk costs (you already have a data center), but for a smaller shop they might matter. If you had to pay co-location fees for rack space or high electricity costs, the math could shift slightly. AVS’s pricing includes all those infrastructure overheads of running in Azure’s data center. If, for example, an organization is closing down its on-premises data center entirely, AVS could avoid the need to maintain any server room – an intangible savings (or avoidance of a cost) that might justify its price.

Opportunity Cost of CapEx: Spending $80K on infrastructure now versus spreading it over 5 years could be a decision of financial strategy. Some companies simply prefer predictable monthly expenses to large depreciating assets. In such cases, even if the sum of monthly payments is higher, the model might fit their accounting or cash flow needs better. That’s a business decision beyond pure TCO.

In this post, we focused on pure cost efficiency in hard dollars, and by that measure, the classic on-premises approach clearly wins for a 100 VM steady-state workload. The more you can leverage existing investments (reusing licenses, repurposing hardware, etc.), the bigger the cost gap in favor of CapEx models. Microsoft’s own messaging acknowledges this: if you already own Windows Server Datacenter, you essentially have a full virtualization stack at no extra cost – a compelling story for Hyper-V. Azure Local introduces ongoing fees for added benefits, so it needs to earn its keep; with AHB you can mitigate those fees and still enjoy the newer tech, which is an attractive middle ground. Azure VMware Solution, while expensive, targets scenarios where speed and continuity trump cost – such as an urgent data center exit or avoiding a massive VMware relicensing due to price hikes (the so-called “VMware tax” many are trying to escape).

Conclusion: CapEx vs. Subscription – Which Wins?

For the specific question posed – “Which stack is cheapest over five years for a 100 VM footprint?” – the answer is straightforward: the traditional CapEx model of on-premises Hyper-V (or Azure Local using existing licenses) offers the lowest TCO in our analysis. You’re looking at on the order of $80K-$90K spent, versus several hundred thousand with the cloud-based options. If pure cost minimization is your goal and you have the up-front budget, it’s hard to beat running your own infrastructure with Windows Server and Hyper-V.

However, it’s important to frame this finding in context. The allure of subscription-based models (be it Azure Local’s pay-as-you-go or AVS or other clouds) lies in what they provide beyond raw compute: easier management, fast deployment, eliminating big upfront purchases, and access to additional services. An organization must weigh those factors against the budget impact. Many find that for stable, long-term workloads, CapEx-heavy investments pay off financially, whereas cloud makes sense for variable or strategic workloads despite the premium. In fact, as one IT professional noted, if your servers are on 24/7 doing the same thing, cloud is usually not the cheaper route. Our 100 VM scenario is exactly that kind of steady state – hence on-premises wins.

Key takeaways:

- Hyper-V on Windows Server (with Datacenter licensing) remains extremely cost-effective – essentially a one-and-done cost for five years of virtualization. This is a big reason why many organizations “avoid the VMware tax” by sticking with Microsoft’s stack.

- Azure VMware Solution, while offering a quick path and no retraining, comes at a very high ongoing cost. It can be 3–5× more expensive in TCO vs. on-premises solutions. It’s best justified for short-term migrations or specific use cases (e.g., disaster recovery, temporary capacity) rather than as a cost-saving measure.

- Azure Local occupies a middle ground. In pure pay-go form, it costs more than do-it-yourself Hyper-V, but much less than AVS. If you take advantage of Azure Hybrid Benefit, you can bring it nearly on par with Hyper-V cost-wise while gaining some cloud-like perks. Essentially, Azure Local lets you decide to go CapEx or OpEx with the software – giving financial flexibility.

In the end, the “cheapest stack” for 100 VMs over 5 years is the one where you invest upfront in ownership: your hardware, your licenses, your control. That said, cheapest isn’t always best for every scenario – but it sets a baseline. Organizations should crunch their own numbers with these models, insert their actual costs (including things like data center overhead or existing license inventory), and make an informed decision. The good news is Microsoft’s ecosystem now offers a spectrum from pure CapEx (Hyper-V on Windows Server) to pure OpEx (AVS cloud), with Azure Local enabling a bit of both. You can choose the model that fits your financial strategy, while still leveraging Microsoft’s virtualization technology underneath.

In the next post in this series, we’ll delve into licensing models in more detail – demystifying per-core vs per-socket vs per-subscription licensing and how those impact planning. So stay tuned for Post 2, where we make sense of the licensing maze and how it affects your modernization journey.

References

Microsoft Official Pricing and Documentation

Microsoft Azure VMware Solution Pricing - Azure official pricing calculator and documentation. East US region pricing estimates for AV36 hosts at approximately $6-8 per hour pay-as-you-go rates.

Windows Server 2025 Datacenter Edition Licensing - Microsoft Volume Licensing Reference Guide. 16-core license packs with MSRP approximately $6,000-$6,600 per pack.

Azure Local Pricing - Microsoft Azure pricing documentation. Host fee of $10 per physical core per month, Windows Server guest licensing at $23.30 per core per month.

Azure Hybrid Benefit Program - Microsoft licensing documentation detailing how existing Windows Server Datacenter licenses with Software Assurance can be applied to Azure Local and Azure VMware Solution.

Industry Pricing Observations and Regional Data

UK Azure VMware Solution Pricing - Public pricing estimates showing £18,500/month for 3-node pay-as-you-go configuration, reducing to approximately £9,000/month with 3-year reservations. Source: Microsoft partner pricing observations.

Azure VMware Solution Reserved Instance Discounts - Microsoft reservation pricing showing approximately 60% savings with 3-year commitments compared to pay-as-you-go rates.

Enterprise Server Hardware Pricing - Industry standard pricing estimates for mid-range 2-socket servers (2×16-core CPUs, 512-768 GB RAM, NVMe storage) at approximately $15,000 per server including 5-year support contracts. Based on Dell, HPE, and Lenovo enterprise server configurations.

Previous Blog Post Reference

- “Beyond the Cloud: The Case for On-Premises Virtualization” - Previous post in this series exploring post-VMware virtualization strategies. Available at: https://thisismydemo.cloud/post/rethinking-virtualization-post-vmware/

Industry Studies and Best Practices

Cloud vs On-Premises Cost Studies - Multiple industry reports and anecdotes consistently showing 3-5× higher costs for steady-state workloads in cloud environments compared to on-premises equivalents. Sources include Gartner, Forrester, and various enterprise case studies.

Software Assurance Pricing - Microsoft Volume Licensing estimates showing Software Assurance at approximately 20-25% of license cost annually.

Azure Local Validated Hardware Program - Microsoft’s catalog of 200+ validated node configurations from approved hardware vendors.

Technical Specifications and Architecture

Azure VMware Solution Node Specifications - Microsoft documentation for Azure VMware Solution 36-core (AV36) (36 cores, 576 GB RAM, ~18 TB storage), Azure VMware Solution 36-core Plus (AV36P) (enhanced memory), and Azure VMware Solution 52-core (AV52) (52 cores, 1.5 TB RAM) node types.

Storage Spaces Direct Documentation - Microsoft technical documentation for hyperconverged storage architecture used in Windows Server Failover Clustering.

Windows Server Failover Clustering - Microsoft documentation for Windows Server Failover Clustering (WSFC) technology and Hyper-V integration.

Cost Analysis Methodologies

Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) Framework - Standard IT cost analysis methodology including CapEx (Capital Expenditure) and OpEx (Operational Expenditure) components. Referenced from Microsoft Cloud Adoption Framework.

Azure Cost Management Best Practices - Microsoft recommendations for cost optimization in hybrid and cloud scenarios.

Note: Pricing figures and estimates cited in this analysis are based on publicly available information as of June 2025 and may vary by region, volume licensing agreements, and current market conditions. Organizations should consult current Microsoft pricing and their specific licensing agreements for accurate cost planning. Windows Server 2025 pricing reflects modest increases over previous versions, and Azure service pricing is subject to change.